Canales chosen as May 2014’s “Author of the Month” on Houston Public Media

Canales chosen as May 2014’s “Author of the Month” on Houston Public Media

Houston Public Media radio host Eric Ladau interviewed Canales for its website’s “Arte Público Press Author of the Month” feature, and along with the transcript, their conversation is available to listeners on the station’s interactive site through on-demand audio streaming here.

Click here to see all Arte Público authors featured on Houston Public Media.

About the Author:

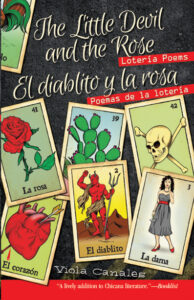

VIOLA CANALES, a native of McAllen, Texas, is a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School. She spent four years in the U.S. Army as a commissioned officer and has worked as a litigation and trial attorney. President Bill Clinton appointed her to the U.S. Small Business Administration, where she oversaw the delivery of programs and services for numerous states in the southwest region. Canales is the author of Orange Candy Slices and Other Secret Tales (Piñata Books, 2001); The Tequila Worm (Random House, 2005), winner of the 2006 Pura Belpré Medal; and The Little Devil and the Rose: Lotería Poems / El diablito y la rosa: Poemas de la lotería (Arte Público Press, 2014). She currently lives in Stanford, California.

About her latest book, The Little Devil and the Rose: Lotería Poems / El diablito y la rosa: Poemas de la lotería

In her ode to “The Umbrella,” Viola Canales remembers a family story about her mother, who every Saturday as a child “popped open her prized child’s bright umbrella / as did her little sister / and followed their mother’s adult one / from their Paloma barrio home / to downtown Main Street McAllen / walking like ducks in a row / street after street,” until one Saturday “the littlest one disappeared / inside the wilderness of Woolworth’s.” Warm-hearted recollections of family members are woven through this collection of 54 poems, in English and Spanish, which uses the images from lotería cards to pay homage to small-town, Mexican-American life along the Texas-Mexico border.

In her ode to “The Umbrella,” Viola Canales remembers a family story about her mother, who every Saturday as a child “popped open her prized child’s bright umbrella / as did her little sister / and followed their mother’s adult one / from their Paloma barrio home / to downtown Main Street McAllen / walking like ducks in a row / street after street,” until one Saturday “the littlest one disappeared / inside the wilderness of Woolworth’s.” Warm-hearted recollections of family members are woven through this collection of 54 poems, in English and Spanish, which uses the images from lotería cards to pay homage to small-town, Mexican-American life along the Texas-Mexico border.

Cultural traditions permeate these verses, from the curanderas who cure every affliction to the daily ritual of the afternoon merienda, or snack of sweet breads and hot chocolate. The community’s Catholic tradition is ever-present; holy days, customs and saints are staples of daily life. San Martín de Porres, or “El Negrito,” was her grandmother’s favorite saint, “for although she was pale too / she’d lived through the vestiges of the Mexican war / the loss of land, culture, language, and control / and it was El Negrito to whom she turned for hope” to bring enemies together.

Fond childhood memories of climbing mesquite trees and eating raspas are juxtaposed with an awareness of the disdain with which Mexican Americans are regarded. Texas museums, just like its textbooks, feature cowboy boots worn by Texas Rangers, but have no “clue or sign of the vaqueros, the original cowboys / or the Tejas, the native Indians there.” And some childhood memories aren’t so happy. In “The Hand,” she writes: “In the morning I arrived at my first-grade class / knowing no English / at noon I got smacked by the teacher / for speaking Spanish outside, in the playground.”

Inspired by the archetypes found in the Mexican bingo game called lotería, these poems reflect the history—of family, culture, and war—rooted in the Southwest for hundreds of years.